Houses are loaded: actions of intimacy, decadence, indecency, and humanity take place inside walls of stone, metal, wood, and glass. But what of the space itself, where events happen, where emptiness defines the surrounding physical elements? Is it possible to have a visual relationship with something we cannot see? Where a familiar Victorian structure once stood, Rachel Whiteread has left only a concrete object. After using the frame of the home as a mold for the new structure, Whiteread removed the traditional exterior materials to reveal a new solid object in the space and shape of the old domicile's interior. Imprints of windows and doors leave traces and the audience must re-evaluate its relationship with the space: emptiness is now solid and a solid form is now empty. Whiteread reveals, in fact, that nothing has always been something. Whiteread's works often intimate that something has been lost, but sometimes they reveal the opposite -- sometimes the viewer discovers something they always knew existed but could not identify visually. Her sculptures investigate the relationship between matter and its corresponding negative space, between what we have imagined lost and what we have discovered found.

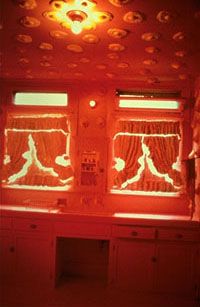

Judy Chicago - Womanhouse (1971)

Women's labor formed the subject matter of Womanhouse, a large scale cooperative project executed [as part of] the Feminist Art Program at CalArts where Judy Chicago, in collaboration with CalArts instructor Miriam Schapiro (Chicago had moved the program which she founded in 1970 at Fresno State College to CalArts in the fall of 1971), [took] an abandoned Hollywood house [and] transformed [it] into a series of fantasy environments. Womanhouse explored and challenged - with a complex mixture of longing, nostalgia, horror, and rage - the domestic role historically assigned to women in middle-class American society.

The Nurturant Kitchen dramatically evoked the exhaustion and degradation of women trapped in selfless service to others. Dozens of foam-molded fried eggs descended its sickly pink walls from ceiling to floor, gradually metamorphosing into pendulous breasts, a metaphor for the burden of perpetually feeding and nurturing others.

"In order to express unbearable family tensions, I had to express my anxiety with forms that I could change, destroy, and rebuild."

The family home, the network of relationships among the members of the family, and the child's anguish make up the "childhood motivations" which are the basis of Louise Bourgeois' art. "Domesticity is very important. I think it is overwhelming. It has to be practical, patient and skilled," she writes. In Louise Bourgeois' work, we are often faced with the presence of subjects that are not immediate figures of desire but they position themselves clearly as operations of desire. The world of Bourgeois' sculptures is that of tangibility. "This is not mere 'parole antique.' I work with the present. Eternal, universal and ever-present emotions. Especially the emotions of violence, jealousy and fear."

Bourgeois' sculptures often blur the distinctions beween interior and exterior, between body and mind and explore the nature and function of memory. Still productive even in her nineties, her work continues to speak to the ways we use our bodies and minds to construct identity-making experiences out of social interaction.

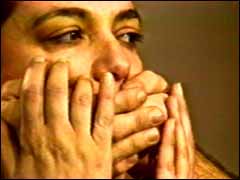

Mona Hatoum - So Much I Want To Say (1983)

Mona Hatoum's art invites us to experience anew the cultural intersections that link our identities with the physical and perceptual world surrounding us. Hatoum employs a wide variety of media and techniques, but her unique minimalist style is characterized by forms and materials that evoke feelings of intimacy and familiarity, while simultaneously suggesting the possibility (whether real or imagined) of physical danger.

In the performance Under Siege (1983), parts of which are included in the 1984 video Changing Parts, the artist struggled in vain to release herself from a container, generating an anxiety that suggests the agony of entrapment. When Mona Hatoum was 23, she came to England on a visit and stayed on when the outbreak of civil war in Lebanon prevented her returning. While the conflict was raging during the seventies and eighties, she feared for her family's safety and rarely saw them. For long periods it was impossible to phone them, or even to be sure they would receive her letters. Meanwhile she was living in London, effectively an exile. Her video, So Much I Want To Say (5 min. b/w video, Western Front Video Production, Vancouver, Canada), was made during this time. A series of still images unfolds (one every eight seconds), revealing the face of a woman (the artist) filling the screen. Two male hands repeatedly gag the woman and obscure parts of her face, sometimes covering it completely. On the sound-track, repeated over and over again, are the words "so much I want to say" spoken by a female (Hatoum's) voice.

Martha Rosler - Semiotics of the Kitchen

Since the early 1970s, Martha Rosler has used photography, performance, writing, and video to deconstruct cultural reality. Describing her work, Rosler states, “The subject is the commonplace; I am trying to use video to question the mythical explanations of everyday life. We accept the clash of public and private as natural, yet their separation is historical. The antagonism of the two spheres, which have in fact developed in tandem, is an ideological fiction—a potent one. I want to explore the relationships between individual consciousness, family life, and culture under capitalism.” Avoiding a pedantic stance, Rosler characteristically lays out visual and verbal material in a manner that allows the contradictions to gradually emerge, so that the audience can discern these disjunctions for themselves. By making her ideas accessible, Rosler invites her audience to re-examine the dynamics and demands of ideology, urging critical consciousness of the individual compromises exacted by society, and opening the door to a radical re-thinking of how cultural “reality” is constructed for the economic and political benefit of a select group.

In Semiotics of the Kitchen, from A to Z, Rosler “shows and tells” the ingredients of the housewife’s day, giving us a tour that names and mimics the ordinary with movements more samurai-like than suburban. Rosler’s slashing gesture as she forms the letters of the alphabet with a fork and knife in the air, is a rebel gesture, punching through the “system of harnessed subjectivity” from the inside out. “I was concerned with something like the notion of ‘language speaking the subject,’ and with the transformation of the woman herself into a sign in a system of signs that represent a system of food production, a system of harnessed subjectivity.”

Bill Viola is one of the few contemporary video artists who explores the medium both conceptually and sensually, rather than using it as a narrative document or film substitute. Through dramatic use of space, his installations function less as concrete works and more like enveloping, temporal environments aimed at creating visceral experiences for the viewer -- sort of like Happenings with a rewind button. Viola uses the contradictions between flowing and interrupted time in the video installations assembled for the Selected Works Exhibition.

Toni Dove - Artificial Changelings

Artificial Changelings is the first in a trilogy of responsive movies. It is presented as an installation in which one person at a time uses body movement to interact with sound and images. Viewers can take turns either as particpants or spectators. Artificial Changelings brings the movie off the screen and into the room inviting viewers to engage with characters in an immersive environment. The installation consists of a large curved rear projection screen suspended in a room with four zones delineated on the floor in front and some chairs for a small audience. Non-interactive narrative sequences frame the experience at beginning and end. The body of the piece contains multiple segments that offer the audience an opportunity to have a responsive experience with the characters and environment. The viewer steps into a pool of light in front of the screen and enters the interactive zones. When close to the screen you are inside a character's head; back off and the character addresses you directly; back off again and you are in a trance or dream state; and back off once more to enter a time tunnel that emerges in the other century. Within the zones, movement causes changes in the behaviour of video and sound. There are body, speech and memory segments - each with different behaviors. The characters become like marionettes with unpredictable reactions based on the movement of the viewer in front of the screen. Body movement will dissolve images, shuttle forward and reverse on the time line, trigger frame loops, and change speed and color, as well as dissolve between segments and create superimpositions. Movement close to the screen will produce intimate revelations, close-up images and whispered sounds. Movement away from the screen will create memories clouded by layers of time, transparent images, and washes of sound. The sound environment and emotional tone of the piece are altered as well by the nature of a viewers' movements within each zone. Different viewer responses produce different aspects of content and affect.

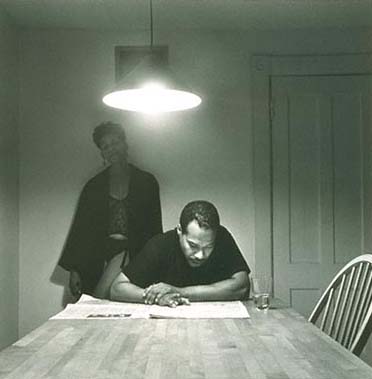

Carrie Mae Weems - The Kitchen Table Series

The work presented in the Kitchen Table Series (1990), supplemented with several related works, was created during a richly productive period between 1987 and 1992. During this period Weems expanded the perspective of her work from the personal (her family's experiences) and the political (racism) to broader issues of gender relations, individual identity, and parenting.

"My work reflects my desire to understand my ex-perience in relation to my family and my family's experience in relation to black families in this country.... I am fascinated by the distances between people in the same family, between men and women, and between ethnic groups and nationalities through the use of language derived from experience. There's a certain language that comes out of sharecropping and cotton farming, that comes out of the way men and women, women and children, and women and women share experiences. That's the vitality of language."

Twenty images and thirteen text panels comprise the Kitchen Table Series, which pivots around the experience of one woman (played by Weems) who appears in every frame. Of the fourteen works (three are triptychs), she appears alone in five works, in another five she is joined by one or more other females, while in the remaining four a gentleman is visiting. The square composition remains constant throughout the series: under a single hanging light, one person appears at the far end of a table. Sometimes he or she is joined by others on the sides. There is always a place for the viewer at the near end of the table, which comes right to the edge of the frame, mimicking a seventeenth century still life compositional strategy used to make a scene more intimate. Yet this device also helps us sense the space as a proscenium theatre, a set where the drama will unfold.

(text from Ana)

Oz Philosophy

"Modern

Space and Domesticity"

The continual

investigation of the idea of space is a driving force in the history of early

modern architecture. But theories of space are abstract and even philosophical

constructs whose actual construction and inhabitation could be problematic (i.e.,

the De Stijl axonometric). On the other hand, the upper-middle-class house has

also preoccupied modern architects in two regards: first, these were the most

sympathetic patrons for modern architecture in Western Europe and America and

these houses served as a testing ground for architectural ideas and innovations.

Second, the construction of a new model for bourgeois domesticity was an inaugural

part of the social project of modernism on a larger scale. How did these parallel

projects, modern space-conception and (upper middle-class) domesticity, intersect?

Architectural space is a

continually developing series of intellectual abstractions

The models of domesticity provided by specific modern houses must be questioned

as psychological and social constructions of a particular kind of family and

class life (family relations and the construction of social boundaries,social

relations within and without the house)

"Reflections

on Domesticity" by Boudon Chavez

"Now, however

— now that I am thirty, and married, and separated, and not so sure I believe

in fate — it's not dread so much as a sort of loneliness I feel, or anticipate,

will be the inevitable consequence of an acceptance on my part that this may

be who I am: a woman without a husband; a woman who, given my ambitions, and

the way I relate (or refuse to relate) to men may never 'have' a family, like

my mother 'had'. It makes me afraid, when I consider this. Without a king in

my narrative, I don't know how to proceed; don't know how or what kind of home/kingdom

I'm to help build, or why. And frankly, I don't want the entire responsibility.

When you're as poor as I am, it's not a pretty prospect: what amount of metaphorical

dick-sucking it will take to get from here to there; from a position of powerlessness

to a position of power in a world owned by men who, in some way or another,

necessarily want to own me. "

"By the time I was born, then, my mother had reason to feel that she had, in effect, not only wasted her entire adult life but done damage by it. Did she ever contemplate re-entering the "workforce"? I don't know. I think, based on things my mother, who is, in a word, acute, has said in the past couple of years, that the thought of entering a workforce filled with mostly younger, better educated women (My mother was forty-six, remember, when she had me.); women whom she imagined had a good reason to believe despised everything she represented — whether they had a right to or not — scared her. Whatever the reason, my mother chose to remain a homemaker to the end; and, I'd say understandably, wanted to believe in the validity of such a choice. "

"My sister Betsy says she remembers a Thanksgiving dinner one year at which my mother threw a baked potato in anger, at someone across the kitchen. At which point, says my sister, she and her husband at the time, Ken, who had just arrived at the party, turned around and fled."

"The

Cult of Domesticity and True Womanhood"

Between 1820 and the Civil

War, the growth of new industries, businesses, and professions helped to create

in America a new middle class. Although the new middle-class family had its

roots in preindustrial society, it differed from the preindustrial family in

three major ways: I) A nineteenth-century middle-class family did not have to

make what it needed in order to survive. Men could work in jobs that produced

goods or services while their wives and children stayed at home. 2) When husbands

went off to work, they helped create the view that men alone should support

the family. This belief held that the world of work, the public sphere, was

a rough world, where a man did what he had to in order to succeed, that it was

full of temptations, violence, and trouble. A woman who ventured out into such

a world could easily fall prey to it, for women were weak and delicate creatures.

A woman's place was therefore in the private sphere, in the home, where she

took charge of all that went on. 3) The middle-class family came to look at

itself, and at the nuclear family in general, as the backbone of society. Kin

and community remained important, but not nearly so much as they had once been.

A new ideal of womanhood and a new ideology about the home arose out of the

new attitudes about work and family. Called the "cult of domesticity," it is

found in women's magazines, advice books, religious journals, newspapers, fiction--everywhere

in popular culture. This new ideal provided a new view of women's duty and role

while cataloging the cardinal virtues of true womanhood for a new age.

"Domesticity:

A Domestic Feminist Stays Home" by Holly Teichholtz

"Although

it's not as if the feminist in me up and moved to Timbuktu, leaving a simpering

domestic servant in her place, there's a difference between a woman's taking

on the majority of the housework (even if she doesn't work) and a man's doing

the same. Men don't carry in their blood and their bones the collective memory

of thousands of years trapped in the home as domestic servants to their spouses

and families. For men, the joy of taking on a household role can be equal to

or greater than that of working outside the home -- not because domestic work

is easier or more pleasant than work outside the home, but because when a man

does it, it carries a symbolic weight of change and non-conformity. Being a

stay-at-home man can be an affirming statement of polite disagreement with history,

a symbol of the determination to live life as one sees fit, regardless of society's

ideas. Being a stay-at-home girlfriend didn't strike me as offering the same

kind of affirmative reinforcement, and it had never been high on my list of

life goals."

"Domination,

Desire & Domesticity"

Domestic environments,

whether today or in the past, evoke multiple associations, from the dread of

a decline in status to a longing for familial intimacy. Experiences and symbols

intertwine with formal rules and tastes.

Technical

Sensors, Interaction & Performance: Creative Uses of Technology in Live Performance - Information on sensors, software, hardware, and MIDI.

Information on the MIDI Brain, CV to MIDI converter, and I-CubeX MIDI controller.

VNS Motion Tracking System specifications by David Rokeby, as well as an introduction to Max (a graphical programming environment for music and media applications) and softVNS.

Liquid effect filter plug-ins (Evolution's WaveWorld and Psunami) for Adobe After Effects at Atomic Power

The sensors used in this project come from QProx™ and are based on the Charge Transfer (QT) principle, a "revolutionary new way to sense capacitance."

(future) Bibliography

• Aungles, Ann. The Prison and the Home: A Study of the Relationship Between Domesticity and Penality (The Institute of Criminology Monograph, No. 5). Sydney: University of Sydney Warren Center, 1994.

• Bachelard, Gaston. The Poetics of Space. New York: Orion Press, 1964.

• Poster, Mark. Critical Theory of the Family. New York : Seabury Press, 1978.

• Visser, Margaret. Much Depends on Dinner : The Extraordinary History and Mythology, Allure and Obsessions, Perils and Taboos, of an Ordinary Meal. New York: Grove Press, 1987.

• Visser, Margaret. The Rituals of Dinner : The Origins, Evolution, Eccentricities, and Meaning of Table Manners.New York: Penguin USA, 1991.