These are five silhouettes of me, traced on butcher paper, each representing a different facet of my life.

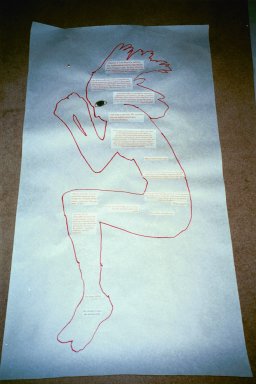

The first one is full of

text from a speech in the play Waiting

for Godot by Samuel Beckett. The speech itself is nonsense, and represents

the bloated thought of academia where by using large words one seems to sound

intelligent but is actually saying nothing. This has been largely my experience

with college; lecture and regurgitation. I feel that it is constantly running in

the background, and I am able to spout out what a professor wants to hear at a

moment’s notice without actually believing any of it.

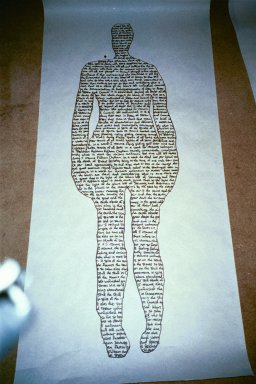

The second is a collage of

audio equipment surrounded by onomatopoetic sounds that the body can make. I am

a fully aural person—my memory is based entirely on what I hear, not what I see,

and I recognize voices and other sounds with great accuracy. I work as a sound

designer for video games, and this equipment—all of which I own or wish I did—is

from an audio magazine I subscribe to.

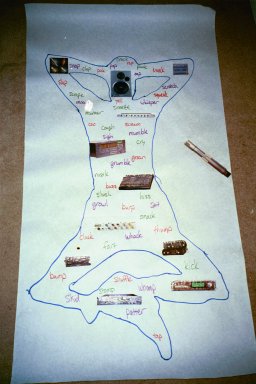

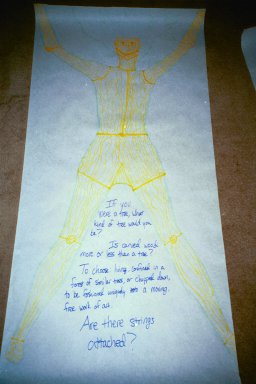

The third is my crude

artistic representation of a wooden marionette, and this was born out of a train

of thought I had which ended in a pun that delighted me. The text reads, “If you

were a tree, what kind of tree would you be? Is carved wood more or less than a

tree? To choose; living, confined in a forest of similar trees, or chopped down,

to be fashioned uniquely into a moving, free work of art. Are there strings

attached?” It is interesting to think of oneself as a puppet, with or without

someone pulling the strings.

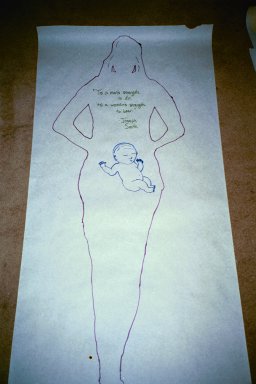

The fourth is symbolic of my

maternal instinct. In considering the body, one must not forget that through our

bodies we pass genes, mannerisms, and personality to new bodies. The quote reads

“It is a man’s strength to do; it is a woman’s strength to bear,” written by

Joseph Smith (founder of the Mormon church.) This quote always fascinated me,

again because of the pun on bearing general suffering, bearing a child, and that

bearing a child is in fact literal suffering.

The fifth I created again

with the idea that we pass on our bodies to our children, but this time it was

in the negative sense—that my mother’s eyes are not my eyes, that we see the

world in completely different ways. It’s an essay about a memory of being nine

years old and discovering this for the first time. The text

reads:

Patterns. It’s all about the patterns. The mathematical patterns that decide each raindrop’s fate. At sixty miles an hour, speeding down the highway, there are so many possibilities. Some slide smoothly and easily in a horizontal line towards the backseat, whose window is being stared right through by my little brother, who has no notion of the complexity of mathematic nuances that combine to deliver those drops—and those drops alone—to his window from mine. Some never make it to the backseat, and weave a jagged line across and down, alternating directions until finally sliding off the bottom of the glass, while others sit perfectly motionless, thought they appear to be the same size and shape as the other drops, which move so rapidly.

I am nine years old. My curious, not-yet-jaded mind races with possibilities. What causes which drops to move where, and when? At this speed, there are still a wide variety of outcomes. But at one hundred miles an hour, the outcomes would be fewer—no no, not fewer, just much less probable. The distribution curve is taller and narrower. Going even faster, towards the speed of light, the distribution would move towards a vertical line, all drops conforming to the average under the impossible impetus of infinity. But if that’s the case, if we can follow the paths with precision at very high speeds, then in theory we must be able to continue to calculate backwards, introducing more variables a few at a time, until we can accurately predict the paths at lower speeds. Even as slow as sixty miles per hour, if one calculated long enough. But it would take more than a lifetime, to account for so many things: gravity, air pressure, ripples in the glass—

“Who won?” My mother interrupts me.

“Huh?”

She smiles knowingly, as if we share the most important secret in the world. “When I was little, I used to pretend the raindrops were racing, too. I’d cheer for the winner—ooh look! That one’s close!...YAY!” she cries, like the cheerleader she never was, as one raindrop, victim to millions of discrete forces of physics, turns downward and reaches the bottom of the window—seemingly randomly, but NOT randomly! “It’s going to be close for second place...”

She keeps talking. My mothers eyes are not my eyes.